Early Livestock Guardian Dogs

Livestock Guardian Dogs 1833

Livestock Guardian Dogs 1833

The earliest evidence of domestication of sheep dates back from 9,000 B.C. The evolution of the Livestock Guardian Dogs we know today corresponds to the gradual migration of nomadic people with their flocks of domestic sheep and goats across Europe from East Asia both geographically and in time. But this specialised role is only about 4,000 years old. So it appears that it took around this time for dogs to become selected for their specialised role to live within mobs of sheep and goats without disrupting them. Modern DNA evidence backs up this theory which shows that the highest genetic diversity of domesticated wolves was available in East Asia to form the basis of this selection[1].

The History of the Livestock Guardian Dog

After comparing a number of sources, research suggests that the most believable reference regarding the beginning of the role of Livestock Guardian Dogs comes from Dr Kovacs who said in essence:

"On the basis of archaeological, geographical, cytogenetic (sheep and goats) and morphological evidences it can be stated that the spreading of Livestock Guardian Dogs of Eurasia is identical with the spreading of sheep both geographically and in time"[2]

Why and When the Livestock Guardian Dog Developed

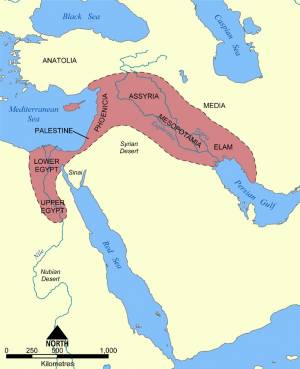

Fertile Crescent c 9,000 BC

Fertile Crescent c 9,000 BC

To understand how and why Livestock Guardian Dogs evolved, it is important to trace their development alongside the early domestication of sheep and goats. When nomadic peoples began to settle, they required dogs of the Molossoid type to guard them from predators. These strong brave dogs later became the various breeds of Mastiffs as well as the Livestock Guardian Dogs we know today.

Around 9,000 BC, people began to domesticate wild animals to become today's breeds of sheep and goats. This ensured a more reliable food source. These formally wild animals lacked aggression, were of a manageable size, had a social nature and sexually matured early with high reproduction rates. But they moved relatively slowly so had no effective natural defence against wolves, bears, wild cats and other wild animals. So in the part of the 'Fertile Crescent' around ancient Mesopotamia, that is Asia Minor and the Middle East, a large and powerful type of dog with a broad mouth was developed to protect domesticated animals in these settled areas.[3]

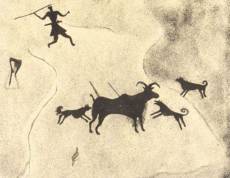

Turkish Cave Drawing c 6,000 BC

Turkish Cave Drawing c 6,000 BC

Interestingly Turkish cave drawings from around 6300 - 5500 BC show a few animals including some large dogs. So although at this time sheep and goats were domesticated, and the Fertile Crescent shown in the map was also becoming occupied by agriculture and early settlements. This decreased the amount of land available for flocks. Around this time the settlements of Mesopotamia grew to become the cross-road to every other part of this ancient world both by land and sea. So, shepherds and their flocks would have had to begin their migration into nearby uninhabited areas.

The Role of the Livestock Guardian Dog

By around 2,000 BC nomadic shepherds and their flocks had migrated in numbers into areas that were not already settled. This was most likely the start of transhumance into mountainous areas to the East of the Fertile Crescent. So it appears that at this time the role of Livestock Guardian Dogs became vital. As protection against predators was essential in this unknown country, this migration would have had to assume a reliance on the nomads' Livestock Guardian dogs that would instinctively fill one or both of these roles which were to

- Guard the nomadic people and live within their flocks of domestic animals, not disrupting them. Instead they safeguarded wild predators such as bears, wolves and large wild cats

- Herd stragglers back within the flock, so keeping them bunched together

Early Trade routes through Eurasia

Early Trade routes through Eurasia

By around 2000 BC it was written in the Genesis iv.2, the first book of the Bible

'Abel was a keeper of sheep'

During the next millennium, trade had spread both ways to and from Asia to the Middle East along a route that became the 'Silk Road' to the area where the Tibetan Mastiff had already developed separately as a Livestock Guardian Dog.

So it appears that the role of the Livestock Guardian Dogs has developed independently in different areas, together with the spread of various civilisations. During the Middle Ages (from 6,000 AD to 15,000 AD) guardian dogs became famous throughout Europe for their use with livestock, such as sheep and goats[6].

How Livestock Guardian Dogs Developed

Sheepdog c 1790

Sheepdog c 1790

By 1,000 BC villages had developed from the Fertile Crescent along other defined trade routes as well as the 'Silk Road' shown by the yellow line in the accompanying map (please click to enlarge). As the horse was primitive at that time, these nomadic people often travelled between villages mainly on foot. So, these ancient trading routes developed slowly and gradually village by village and it appears likely that nomads spread from these ancient routes into unknown territories, together with their flocks and Livestock Guardian Dogs.

Sheepdog c 1803

Sheepdog c 1803

As generations of sheep and goats slowly drifted along these trading routes which spread in all directions from the Fertile Crescent and beyond, generations of Livestock Guardian Dogs accompanied them. So both the dogs and flocks would have adapted according to the immediate surroundings. This trading went as far as Egypt which was part of the large Assyrian Empire at that time and some could have spread further by the sea faring Phoenicians. However, mostly this migration was on foot as these nomads also migrated further into Europe.

When Livestock Guardian Dogs Developed

Spanish Mastiff among a flock

Spanish Mastiff among a flock

According to the Roman scholar Marcus Terentius Varro (116-27BC)[5], livestock guardian dogs were used at that time. He wrote that they probably descended from a Molossoid type of dog that was generally white so it could be more easily distinguished at night and be less likely to be unintentionally mistaken for a wild animal and injured by a huntsman. They were worked either alone, in pairs of one male and one female, or in the case of particularly large flocks several of these Livestock Guardian Dogs could be used. These dogs were carefully bred from families of dogs that bonded instinctively with the flocks of sheep, rather than with the shepherd who cared for them. So strong was this bond, it was recorded that if the shepherd wished the dog to follow him instead of the flock, he must throw the dog a boiled frog!

Spanish Mastiffs in a Mountain Valley

Spanish Mastiffs in a Mountain Valley

Transhumance

This is the movement of domestic stock to find sufficient food. As civilisations moved from East to West and settled in more fertile areas, the movement of this stock was often into the highlands in summer, and into the lowlands or plateaus in winter. There are nomadic people in Turkey who still live with their dogs, sheep and donkeys and practice transhumance in the tradition of their ancestors[4]. This provides an opportunity to observe this practice and understand the important role these wonderful dogs played.

1) Nomads

These are a nomadic population of shepherds who today still practise the ancestral traditions of transhumance. In summer they set up camp on high plateaus in the mountains near water and green pasture. In autumn, they travel down and camp in the lowlands to avoid the harshness of the mountain winter. These people camp in felt tents made of goat hair. However they do make open shelters with primitive roofing made with branches of trees or other plants for basic protection against sun and rain. The sheep and dogs live outside all year round.

2) Semi-nomads

Sheepdogs leading sheep in single file

Sheepdogs leading sheep in single file

These are semi-nomadic shepherds who are partially settled but also practise transhumance. These shepherds live with their whole families in a village in permanent houses with shelter for their flocks in winter. But in summer one of two practices occur

- Either the shepherds together with their entire families travel to the green pastures of the highlands near water sources and live in traditional tents or

- When the shepherd observes the sheep demonstrating their distress from the hot sun by forming a line or queue each trying to hide his head under the tail of the one preceding it, he moves them. This may take many days. At the head of the line is usually a goat which is not so bothered by the hot sun.

When the shepherd finds respite from the sun with a water source, some trees, large rocks, or a primitive purpose built shelter the sheep spend the summer grazing under the stars. At night, the shepherd sleeps in his traditional felt clothes which serve as a sleeping bag while the sheep and dogs remain nearby. The children and the elderly use a donkey to visit the shepherd with supplies. These 'visits' are also social occasions and serve as an opportunity to exchange news.

Spanish Mastiff leading Sheep

Spanish Mastiff leading Sheep

3) Permanent settlements

These are shepherds who are permanently located in more fertile regions. But local climate still plays an important role. In summer in temperate climates, at sunrise the shepherds accompanied by their dogs go through the village from one end to the other gathering sheep from each house to form a single herd. The animals are so used to this practice, they are happy to join the flock and spend the day grazing. At night, children wait in front of their houses to receive sheep belonging to their family.

In areas where the scorching heat during the day makes life difficult for the herd, this procedure happens in reverse when departure occurs towards evening, returning the next morning.

The Traditional Role of the Livestock Guardian Dog

Anatolian (Turkish) Shepherd Dog with Sheep

Anatolian (Turkish) Shepherd Dog with Sheep

The traditional nomad shepherd created the Livestock Guardian Dog we know today with his uniform dominant color blending into the terrain and the flock. Then the predators find him difficult to spot. But the dog's most important role is to create an unbreakable bond with his herd and protect it.

This dog lives among the flock at all times with his role being to guard them from all predators which consist of foxes, wolves, wild cats and human thieves. Mutton is the preferred prey of these predators and because sheep are domestic animals, they have never learnt to defend themselves or outrun predators. So the dogs' role is essential for pastoralism to survive in this wild environment.

The majority of these dogs live outside all year round. Constantly at work, the dogs do not have much opportunity to rest. They have to be vigilant at night as predators know how to use darkness to their advantage. Although some dogs stick close to the shepherds, most patrol the flock from its perimeter, choosing for themselves the locations best suited for optimal monitoring. These dogs observe everything so that they are not caught by surprise. Often there are one or two dogs patrolling farther away from the flock. These dogs were athletic enough to chase wolves when they flee, but heavy enough to fight them if necessary.

Pryenean Mountain Dogs with Goats

Pryenean Mountain Dogs with Goats

The traditional nomads require a dog with a constitution that allows him to adapt to the harsh environmental conditions of the terrain. This means he has to be big and strong enough overcome his predators, fast enough to control the space around him, and durable enough to work in any conditions of weather or terrain. He is alert enough to frighten either an animal or a human thief, but discreet enough not to frighten the family of the shepherd in charge of the flock. He is of a colour which blends into the flock during the day, but does not stand out at night. As these dogs never see a vet, they must also have a remarkably strong constitution.

But what is most difficult to understand is the versatility of their intuition. Within each flock there would be Livestock Guardian Dogs which had the instinct to outwit cunning predators preferably without causing a fight. But some of these dogs could also instinctively notice any member of the flock that has strayed and direct it back into the flock.

These two very different roles have been performed by these wonderful dogs for hundreds of years without direct human direction or intervention.

References and Further Reading

Jane Harvey 'Anatolian? Kangal? What next?' Dog News Australia, published by Australian Canine Press Pty Ltd Australia NSW April 2012 Pages 4 and 8 also refer to Editorial Page 2

[1] Savolainen, Peter; Ya-ping Zhang, Jing Luo, Joakim Lundeberg, and Thomas Leitner (2002-11-22). "Genetic Evidence for an East Asian Origin of Domestic Dogs"

[2] Andras Kovacs, 2000 'The Kuvasz', kuvaszinfo.com/kovacs.htm

[3] Fred Wendorf, Romuald Schild and Associates, 'The Archaeology of Nabta Playa', Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1st Edition 2001, ISBN 978-1-4613-5178-8, Springer Science+Business Media New York, Pages 619-620

[4] Selim Derbent and Dr Orhan Yilmaz, 'Le Karabash, Chiens de Bergers Nomades, son Histoire, son Travail, Son Avenir' Self Published IBSN 978-975-92133-8-9 Chapter 22 Pages 93 - 98 Information suppled by Mr. Ramazan KIVRAK, a Turkish Shepherd and researcher on lifestyle and ancient Turkish traditions.

[5] Marcus Terentius Varro (116-27BC) - 'Rerum Rusticarum' (On Agriculture) from his book translated by William Davis Hooper and Harrison Boyd Ash and published by William Heinemann, London and Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1934

[6] Benoît Cockenpot - 'Le Montagne des Pyrénées' , PB Editions, 1998. p15